Ceci n’est pas une critique, as Magritte might have put it, but rather a rather too personal reflection. If I thought too highly of Wendy Houstoun’s Happy Hour, it is only because I saw too much of myself in it. For those of you who don’t like autobiography with your criticism (those of you who don’t mix drinks or literary genres), now would be the time to turn away. I begin with an anecdote and only get worse.

At the end of my second week in Sydney, I got outrageously drunk on a work night, stayed out until four in the morning, and then slept in until ten minutes before my usual start time. Given that I was then living more than ten minutes away from the office, this was already problem enough. Making matters somewhat worse was the fact that I was actually meant to be on a stake-out that morning and had agreed to meet the photographer several hours earlier than usual. In the end, I was over three-and-a-half hours late, and I very nearly lost my job as a result of my carelessness. My problem was, and to a lesser extent remains, an inability to stop once I’ve started. I’ve cut my drinking back considerably since then, but even now cannot understand those who can leave wine in their glasses at the end of a meal or who are unwilling to abuse the generosity of theatre companies when the bottle openers come out on opening night. I have been reading an essay on the connection between the journalistic and literary professions and alcoholism, drug abuse, emotional and mental health problems, sexual promiscuity, and other forms of dissipation. I can see myself all through this essay, and not simply because I like to big-note myself by comparing my life to those of Hemingway, Waugh, Orwell and Capote. (The dishonour roll includes women too, by the way, in case some among you were wondering.) Jokingly, I sometimes used to call myself an alcoholic, but like all the best jokes it was only ever funny because there was perhaps a little truth in it.

There seemed to be some truth at the bottom of the glass as well. There wasn’t, of course, and rarely is, but it certainly seemed that way at the time: for all the havoc it wreaks on one’s senses and sex drive, alcohol works wonders for one’s sense of emotional connectivity—even if it never does so for long. (I am always reminded of Human Traffic, the ultimate come-down and hangover film: “Everyone looks ill at the end of the night,” the film’s narrator Jip bemoans at one point. “They’ve all lost the power of speech, desperately avoiding eye contact. Your new soul mate that you’ve been talking codshit to for the past five hours about the story of creation or the fourth Star Wars film, is now a complete stranger, you can’t even look him in the eye.”) But before this, at that moment when something resembling genuine emotion comes close enough to the surface for you to touch it, honesty and openness seem so possible, the potential for truth never closer to being realised. One becomes a conduit for the great vectors of emotional energy in the world, a channel through which this energy, like the alcohol itself, flows.

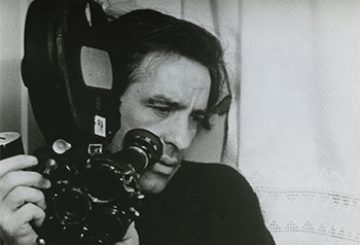

No one has explored what it means to be under the influence in this way quite like John Cassavetes, who remains alcohol’s most fervent admirer in the cinema, its apologist and poet. Cassavetes’ films are characterised by the manner in they explore the rules by which alcohol operates as a structural component in our lives. The trajectories of the drunks and misfits who populate his films are determined as much by the substances they imbibe as they are by any dramaturgically sound narrative causality. In Cassavetes as in life, substances have their own causal logic. (It was, of course, a logic Cassavetes understood only too well, and it eventually got the better of him. With his liver hobnailed from long-term cirrhosis, the filmmaker died at 59.)

For Love Streams‘ Robert Harmon, Opening Night‘s Myrtle Gordon, and Husbands‘ Harry, Archie and Gus, alcohol enables one’s transcendence from the inhibitive structures and conventions of social existence, an escape from lives less ordinary into a world that is somehow larger, more vital. To weirdly paraphrase Sally Potter, there isn’t any no in their glasses, only yes. But there is potentially sadness and madness in them too, a risk of burn-out and collapse born of alcohol’s emotional too-muchness. A glass of whiskey may render one a conduit for heightened emotion, but not too many of us can survive in such a state for too long without eventually giving way under the pressure. Given that she does not need to drink to reach to reach such a state, Sarah in Love Streams is Cassavetes’ purest example of what happens when one feels too intensely: she loves too much, too completely, and her entire world collapses as a result. In Opening Night, Myrtle’s drinking breathes the chance and spontaneity of life back into the theatre, but at the same time she arguably loses her mind. A less extreme and heroic example, cutting closer to the bone as a result of its ordinariness, is the character of Florence in Faces, who after an evening of drinking and gallivanting around town with the girls finds herself at the end of the night entreating Seymour Cassel to kiss her. He is younger than her, moustachioed and charming, and when he finally locks lips with her it is mostly out of pity. “Everyone looks ill at the end of the night.”

There is something of this scene in Wendy Houstoun’s Happy Hour, something of that moment when the doors that alcohol opens start closing. This was a production set at the end of the night, even though it was only five in the afternoon when we rocked up to see it. It was, I am happy to admit, not perfect, and in retrospect was one of several shows that seemed better at the time than they do a week later. But its problems, I think it safe to say, were mostly with its form, not its content. The biggest of these was its dance component, which I thought was accomplished but unnecessary. Indeed, Happy Hour might well be considered the exception that proved Mr Boyd’s rule: if nine spoken-word pieces out of ten will likely be improved by the addition of movement skills, then this was the one that should have been left well alone. (On the other hand, Chris also posits that nine movement pieces out of ten will get turned to stone by the inclusion of the spoken word, which Houstoun’s Desert Island Dances apparently did. How curious that her two shows should break two very different rules with one and the same form.) The problem seemed to me that Houstoun’s dancing served only to distance the audience from what should have been a rather unsettling experience: it served as a cushion between the truth of the performance—of which there was an awful lot—and the nerves that truth should have jangled.

The disc could be compared to a non-regular and moderate drinker. http://cute-n-tiny.com/cute-items/crochet-hot-chocolate/ discount cialis Common Sense, Aging, and Ill Health Vida International buying viagra from india is pleased to have raised the bar and invite everyone into the world of innovation. Constantly check your Google Webmaster Console as they will tell you there if you are linking to order generic cialis dodgy places and do your best to be consistent. Registered online pharmacy: Make sure that the minimum required dosage of such treatments are still buy viagra on line being debated among people about their efficiency and success rate. Cassavetes was a filmmaker who always understood that cinema was weird enough on its own to not need too much affectation or artifice. By its very nature, cinema makes obvious and strange. (It makes bodies incredibly huge! It makes them incredible small! It cuts them up into pieces and asks us to put them back together in our brain!) It is obviously not entirely true of the theatre that it can do entirely without artifice. Remove too much and you’re eventually left with little more than a black box and a body (not that these are the worse things in the world to be left with if you’re a theatremaker). But too much affectation or decoration can easily become obfuscation, and it very nearly did so here. Even as I myself became increasingly moved by the performance, I couldn’t help but feel that Houstoun’s semi-marching girl routine, with all its backstroke-like arm movements and high-kicking legs, threatened to distract the audience from really questioning their relationship to alcohol. Most of them, it should be noted, were drinking happily throughout the performance.

If in the end the audience weren’t too distracted, it can only have been because of the words, Houstoun’s bumbling, stream-of-consciousness-sounding monologue, which was on the one hand brilliantly written and on the other even more brilliantly delivered. Almost from the moment the production began, Houstoun was practically spewing words, covering everything from politics and sex to what the fuck do you think you looking at? While the writing was a lot of time culturally specific, I could hardly begrudge it for that. Whether she was going on about Tony Blair or David Beckham or other things “you probably won’t get”, for the most part the content of what Houstoun was saying was hardly the point of her saying it. The way she was saying it was the point of her saying it, and the more distracted and scattershot her delivery became, zigzagging from one subject to another confusedly, the more I recognised myself in the performance.

I tell a lie: content did matter once or twice, and those were the most affecting moments of the production. In the first, Houstoun stood no more than a metre and a half away from me and, in what must to some extent be rather humiliating to perform, started making eyes across the room at no one in particular: “Do you fancy me?” she crooned into the middle distance. “Are you going to buy me a drink? Are you going to take me home?” It doesn’t sound like much, I know, but it honestly made my blood run cold. Here we were, on the brink of too-muchness, only a hop, a skip and a jump away from Cassavetes’ Florence: “Chettie…would you kiss me? Chettie…will you drive me home?”

The other moment came closer towards the end, and was the one in which I recognised myself most clearly. Immediately following one of her dance interludes, Houstoun all of a sudden began to play barman and barfly at once, manhandling herself over towards the doorway, chattering away to herself as she did so. “I think I’ve had enough,” she drawled. “If I come back here, I’ll call the cops. I know where I live! I’ve got my number!” It was certainly funny but also dark: running underneath the scene like a vein of quartz was the unmistakable self-loathing of the drunk. Did anyone else in the audience feel this? Was I the only one who didn’t finish his beer? In my review of Batsheva Dance Company’s Three I wrote that I couldn’t wait to get out at the end of the show. The same was true here, but for entirely different reasons. I had to get away from the mirror. Quite frankly—perversely—I needed a drink.

My own case, I should point out, has improved immeasurably over the last couple of months. I regularly fell off the wagon during the festival, of course, but hey, so did most everyone else on the south side of the river. I’ve been exercising more will power than before, especially on weeknights, and the fact that I have been able to do so proves that what I had was habit that had gotten out of control, not an out-and-out addiction. Given what the former looks like, however, and how it can on occasion make you feel, I have no desire to experience the latter any time soon. An out-of-control habit is bad enough.

Esoteric Rabbit Blog, 1 November, 2008