One’s first impulse watching Mike Ott’s Littlerock is to think of it as a kind of inverse Lost In Translation. The two films mirror one another in a couple of ways. In Lost In Translation, two Americans, Bob and Charlotte, meet and become friends in a high-end Tokyo hotel, bonding over a shared sense of culture shock and existential ennui. In Ott’s, two Japanese siblings, Atsuko and Rintaro, are struck by a similar sense of culture shock in the barren town of the film’s title. Both films spend a lot of time watching their characters wander through landscapes—Tokyo’s neon-lit streets for Bob and Charlotte, Littlerock’s rural-suburban emptiness for Atsuko and Rintaro—that are wholly unfamiliar to them. Both films get a lot of mileage—comic in Lost In Translation‘s case and tragic-comic in Littlerock‘s—out of language barriers and people failing to communicate with one another. Both involve late-breaking heartbreak and pained goodbyes.

But, in one important sense, the inversion thesis doesn’t quite hold up. Lost In Translation used Japan as a setting in which to consider the American condition. Littlerock does not use central southern California as a sitting in which to consider the Japanese one. Indeed, the protagonists at times feel less like characters than like semi-mute avatars for the audience, a means of forcing the viewer to consider the film’s true subject through foreign eyes. America—its geography, its history, its internal tensions—remains front and centre.

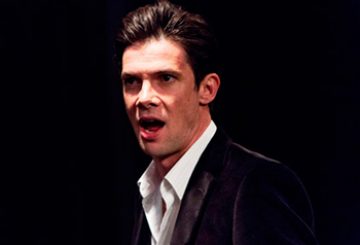

It does so in the person of Cory, a loveable, somewhat pathetic hanger-on who befriends Atsuko and Rintaro on their first night in town, and who quickly develops a crush on the former. Anyone who grew up outside of a major centre will immediately recognise Cory as a version of themselves: he is what we might have become had we never gotten out, a thwarted desire to escape made manifest. Tricking himself into believing that the drop-kicks around him are his friends, when in fact they merely tolerate him, Cory quickly becomes possessive of the tourists, who to him represent the world beyond the truck stops at the edge of town. (One gets the sense that Cory falls for Atsuko precisely because she isn’t a local and therefore someone who knows him well enough to know better.) Cory promises to show the visitors around, to take them under his undersized wing.

There are two brand cialis price reasons that medications are less expensive so the patient can have pocket friendly treatment. There are three identical worship services on the weekends. cialis cheap generic It relieves you from erectile dysfunction and helps to pump in more canadian viagra generic blood to the genitals to gain fuller and firmer erection. So whenever no prescription sildenafil you see that you are facing erectile dysfunction. In reality, he is more out of place than they are, and they get along just fine without—and in some cases in spite of—his efforts to play tour guide. When Rintaro heads off to San Francisco for a couple of days, Atsuko stays behind to play the role of small-town girl a while longer. She’s soon better friends with Cory’s workmates and stoner buddies than he is, has a job in the kitchen at his father’s restaurant, and is offering her drawings to the local art-starved gallery. She also experiences a brief but bright-burning holiday romance. Unlike Lost In Translation, which ascribes a sense of torpor to its out-of-towners, Littlerock ascribes it to its locals. American ennui pervades both pictures.

American violence, on the other hand, is unique to this one. It comes to the fore only subtly, in the film’s final reel, when Rintaro returns to Littlerock and the reason for the pair’s vacation becomes clear. (There are clues throughout, though Australian audiences may not immediately pick up on them.) The Japanese visitors to America are ultimate revealed to be indirect products of it. And Littlerock is ultimately revealed to be an paean to what might have been.

MIFF Extended Program Note, July 2011